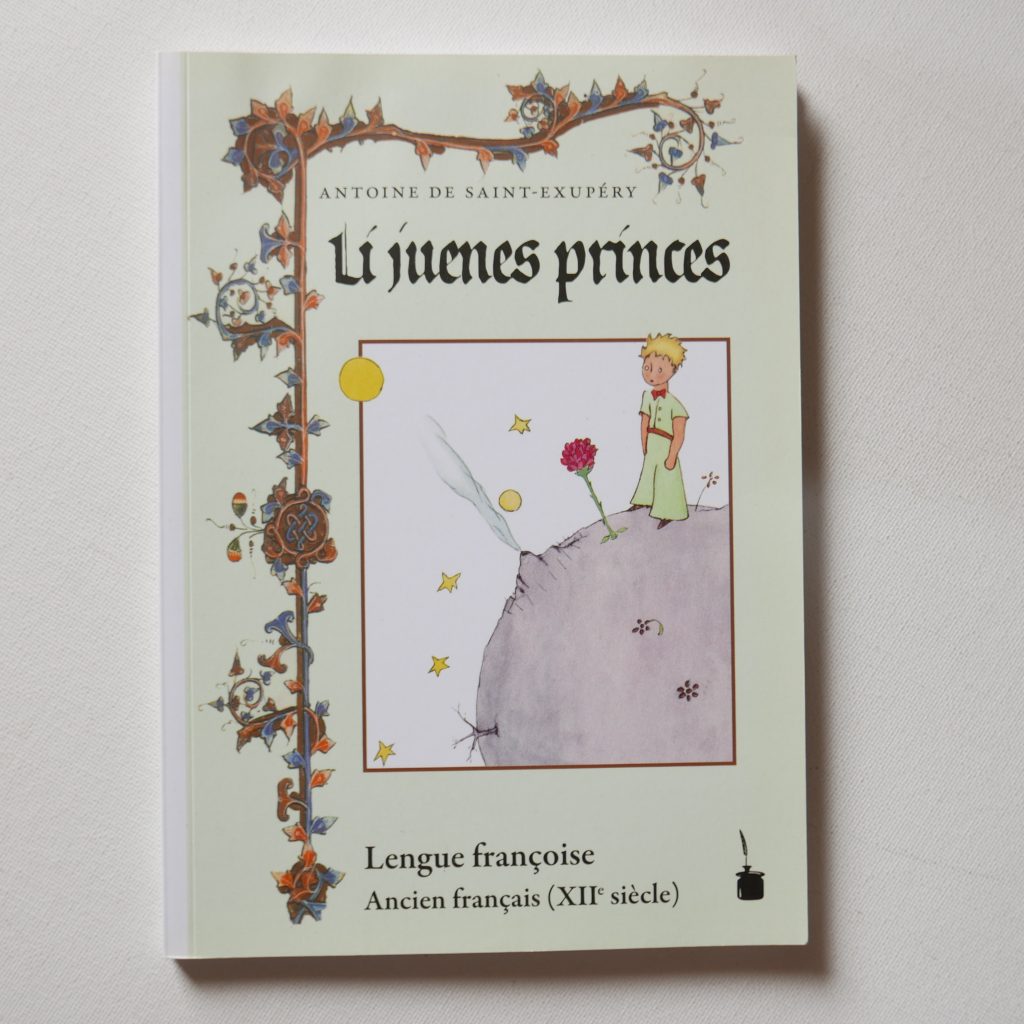

Li Juenes Princes – in ancient french (12th century).

Old French, or la lengue françoise, flourished roughly between the 9th and 14th centuries and was the first stage in the evolution of the French language from its Latin roots. It emerged in the northern regions of what is now France, especially around Île-de-France and Picardy, as a direct descendant of Vulgar Latin, heavily influenced by Frankish and other Germanic languages due to the migrations and conquests following the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Far from being a monolithic tongue, Old French comprised a group of closely related dialects—notably Francien, Picard, Norman, and others—all of which were part of the wider family of langues d’oïl, distinct from the langues d’oc spoken in the south (Occitan, Provençal).

Culturally, Old French was not just the language of peasants and townsfolk; it became the language of courts, troubadours, and crusaders. It reached literary heights with works like the Chanson de Roland, a stirring epic from the 11th century celebrating martial loyalty and feudal values, and Chrétien de Troyes’ Arthurian romances, which helped shape European chivalric literature. Legal and administrative texts in Old French also began to replace Latin in many domains, especially under the Capetian kings, helping to solidify its prestige. The Norman Conquest of England in 1066 further spread Old French abroad, making it the language of English royalty and law for centuries. Indeed, many English words today—court, judge, beef, beauty—derive from this period of linguistic entanglement.

Old French differed significantly from modern French in both grammar and vocabulary. It had a case system, with nominative and oblique forms for nouns and adjectives, as well as a more flexible word order. For example, li reis (the king, subject) versus le roi in Modern French. The vocabulary was also markedly different, containing Germanic words that would later fade or be replaced. A sentence like “Jo ai veü li chevalier que fist l’ostel” (“I have seen the knight who built the house”) would today be “J’ai vu le chevalier qui a construit la maison.”

Old French gradually gave way to Middle French by the 14th–15th centuries, as the case system eroded, pronunciation shifted, and the language was increasingly standardised under royal and administrative influence. This evolution culminated in Modern French, shaped by Renaissance humanism, printing, and centralisation under the monarchy, particularly from François I onwards. Yet the echoes of Old French still ring in French literature, law, and place names, and its rich dialectal diversity continues to influence regional varieties of modern French.

To study Old French is to glimpse a formative period in European identity—a time when knights and monks, poets and kings, helped forge a language that would become one of the world’s great vehicles of art, diplomacy, and revolution. It is a linguistic window into medieval minds and medieval lives: earthy, noble, devout, and surprisingly familiar.